Welcome to the Plastisphere

Sound of a wave

Terry Shibuya: Saving the environment is so important, because the ocean is like a refrigerator, because the ocean has the fishes, the ocean has the Opihe, the ocean has the crabs, the lobsters. So, in our time when we went fishing we would just take what we need. We wouldn’t be greedy and just, you know, would catch the first fish and throw it back. And that would be like a thank you. And then we’d take so much fishes, take it home clean it, eat it, you know, we would just take what we need.

Music by Dorian Roy

Anja Krieger: Welcome to the Plastisphere, the podcast, on plastic people and the planet. My name is Anja Krieger. I’m a freelance radio journalist and ten years ag o I sat in front of my computer in my hometown Berlin, and I read this article. It described a gigantic swirling area of floating trash all the way out in the Pacific. I couldn’t imagine. And I couldn’t let go of this idea that the remnants of our civilization end up all the way in the middle of nowhere. And so I set out on a quest to understand plastic pollution and what we can do about it.

Fast forward a decade and the issue is far from solved. Plastic has been found in Arctic ice, in our soils, in fish, in mussels, in salt, in the air, and even in snow. And we are producing and consuming more and more plastic every single day. It seems like we’re paying a high price for this material we’ve created. And I wonder, is there a way that we can develop a healthy relationship to plastic in the future? Or will plastic be the next thing we will have to phase out, like fossil fuels?

In this podcast series, I want to explore these questions. I will talk to scientists, experts and innovators from the growing global community that works to understand and tackle plastic pollution. But first let me take you on a journey back in time. I’d like to introduce you to some of the people I’ve met and what they have taught me about the issue of plastic pollution.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Ambi from ride to Kamilo beach:

Megan Lamson: Heads down…watch your head, John!

Anja: Kamilo beach is not your usual tourist destination. You have to drive on a super bumpy dirt road for hours to the southern tip of the Big Island of Hawaii. But I wanted to see the infamous plastic beach with my own eyes. And I was lucky to be on holidays.

Ambi

Megan Lamson: So that was the beach heliotroph that was trying to slap us all in the face!

Anja: This was in 2011. Marine biologist Meghan Lamson had taken us along to this remote area with a dozen local kids. She worked for the Hawai Wildlife Fund and organized regular beach clean-ups on Kamilo beach.

Megan Lamson: There are old sayings, . . . wise sayings in Hawaii, that talk about Kamilo as being like a basin for driftwood to wash up and to be the place where people look, to look for loved ones when they wash up the sea. You know, if someone is lost at sea. And so historically that area has been kind of the catcher of things that are floating in the ocean. Back in the day, it was large pieces of heavy wood from other continents, and now unfortunately it’s a lot of plastic.

Anja: It’s a rough and it’s a beautiful place. Black volcanic rock, palm trees, lush green plants, and a wild, windy blue ocean in front of us. And a lot of plastic.

Ambi

Beach cleaners searching in sand

Anja: There were old broken containers, spray bottles for cleaning agents in households, little plastic cages used by fishermen. And the kids even pulled a car seat out of the water. And there was this huge thing in the sand that looked like a rock. It turned out to be a whole bunch of fishing nets. They had probably been burned and clumped together into this kind of new plastic stone.

But the small pieces were the most ubiquitous. Everywhere under our feet, we found tiny and colorful bits of plastic between the old branches and coconuts.

Megan got a big container out of the pick-up and filled it with water to show us how to filter the sand. That way we could see how much small plastic was in there. Hundreds of tiny pieces rose to the surface.

Ambi

Megan Lamson: You wanna grab those, scoop those, real quick! Professional. All right. So here we go! So check this out, we have clean beach sand!

Donna Kahakui: That’s cool!

Anja: One of the women who had come along to the beach cleanup was Donna Kahakui. She ran Kai Makana, a local Ocean NGO, and worked for the Environmental Protection Agency.

Donna Kahakui: I paddled the entire island chain on a one-man canoe, with a goal of trying to educate about our environment.

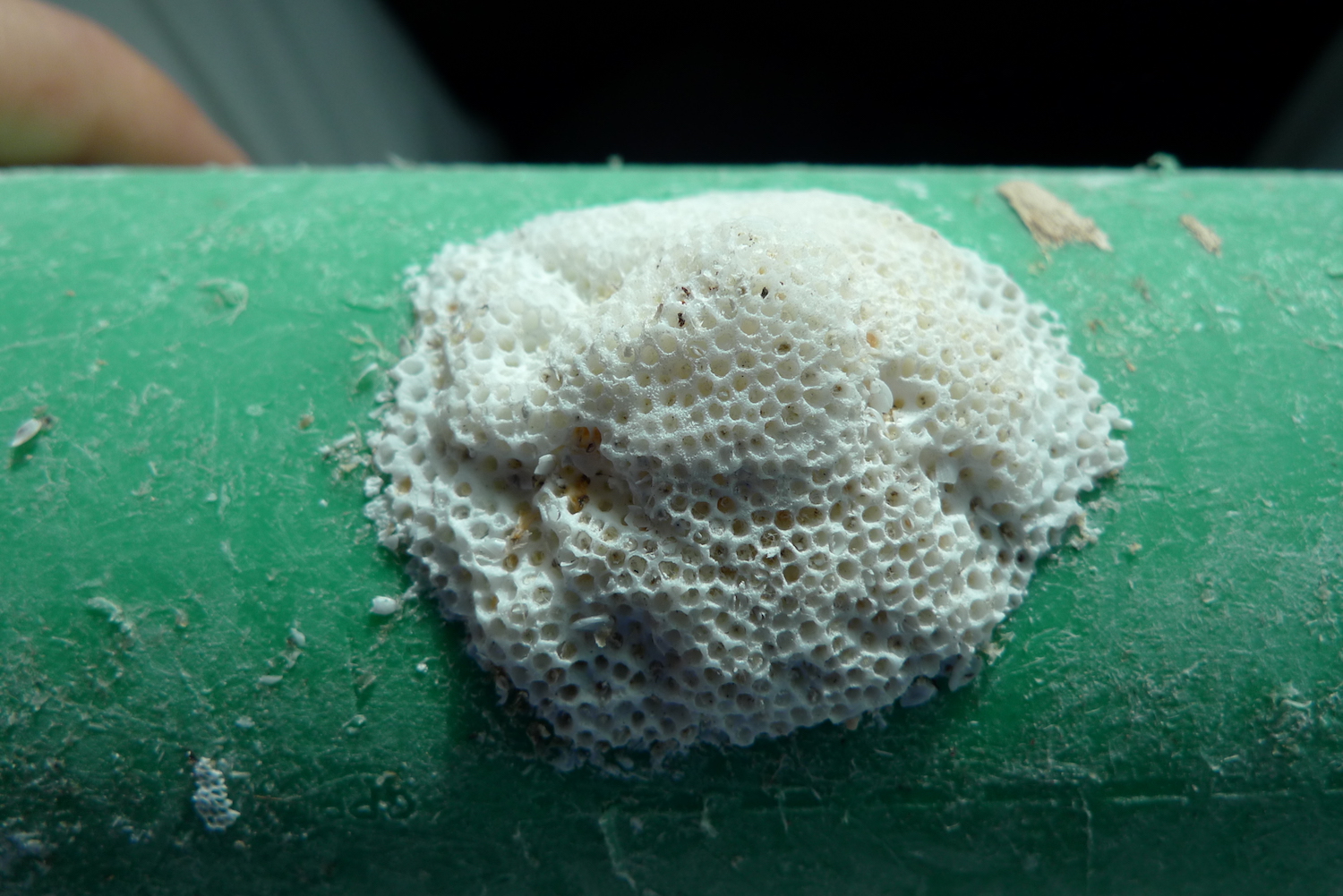

Anja: Donna showed me a pipe that they had just found on the beach. A green plastic pipe with a white intricate structure growing on it. It was the calcium skeleton of a coral that had settled on the plastic.

There’s a chant from the old Hawaiians, the Kumulipo, Donna told me. It describes the creation of the world. The first creature to appear is the coral polyp. And this coral had now settled on our trash.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Nikolai Maximenko: Here on Hawaiian beaches, we have debris from all around the North Pacific. We have pieces that we know are coming from Asia, we have plastic that we know for sure is coming from West Coast of America, of North America. And, of course, we have local products, too.

Anja: On the island of O’ahu, I had talked to Nikolai Maximenko, a researcher with a Russian background at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. Maximenko is an oceanographer and he had started to investigate how plastic behaves in sea currents.

Nikolai Maximenko: Only recently we realized that drifters are kind of marine debris, and now we are using their trajectories. So this is real trajectories of real instruments to study pathways of marine debris.

Anja: Nikolai Maximenko had modelled marine debris and concluded that plastic could end up in these five big ocean currents that exist in all seas. But he had yet to collect the evidence.

Nikolai Maximenko: We know that garbage patches are there. We do not really know where that plastic comes from and where does it go to. In the North Atlantic, it seems that increased production of plastic did not cause increased density of plastic…microplastic in water. So it disappears somehow. And if there is some plastic buried at the ocean floor, it is still to be found.

Anja: In the years that followed there were several studies that found either bigger pieces of plastic or small synthetic fibers and particles in sediment samples on the deep sea floor.

A few days after we visited Kamilo beach in 2011, a huge earthquake shook Japan 4000 miles away. Tsunami sirens echoed over the islands of Hawaii. The gigantic wave that devastated the coast of Japan and took thousands of lives there didn’t hit Hawaii as bad as we thought. But even though the surge quickly subsided, another wave was building up – a wave of trash. The Tsunami had pulled huge amounts of debris into the water, and they had just begun their long journey East across the North Pacific.

Sound of a wave

Anja: We had to say Good-bye to the volcanoes, the monk seal on the beach, the beautiful red ‘Ohi’a trees, the rainbows and the humpback whales. But there was another reason why I would have loved to stay. Just a few days after our departure, a big conference started in Honolulu, the Fifth International Marine Debris conference. Hundreds of experts and scientists searching for knowledge and solutions for the growing pollution of our oceans. But I would get another chance.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja: When you think of a symbol for our plastic age, what comes to mind? For me, it’s plastic bags. In 2012, I visited a factory in Neuruppin, a small town in Germany not far from Berlin. In that little factory, they were producing plastic bags for big supermarkets in Germany, Switzerland Austria and the Netherlands. Millions of them each month! Not the usual kind of plastic bag. But grocery bags made from bioplastics.

Ambi

Plastic extruder machine

Anja: The loud noise that you’re hearing is the extruder. It’s this big machine that produces plastic bags. On one side, they pour in small plastic pellets and some other secret ingredients, and then the machine presses them into large stretches of foil.

Ambi

Ronny Oelke, in German: Greift sich schon ganz anders an, hat eine weichere Haptik.

Anja: Ronny Oelke was the man who took care of the production there, and he told me this biomaterial feels different from normal polyethylene.

Ambi

Ronny Oelke, in German: Man riecht es auch, dass hier Natur drin steckt, das ist jetzt keine Chemie mehr.

Anja: …and that it smells more natural, a bit like French fries, he said. Or a bit like dry hay, I thought.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja: I had become increasingly interested in this topic and was doing research for a radio feature. Could bioplastic be the solution to the plastic pollution problem? German supermarkets sold bags made from this material with slogans like 100 percent composable or smile for the environment! So, I followed these bags to where they were made, to find out more.

Jens Boggel, in German: Ich nehme die Pflanze, gewinne daraus die Stärke, die Stärke wird fermentiert…

Anja: At the plastic bag factory in Neuruppin, I also got to talk to sales manager Jens Boggel. He told me the bags were made from corn starch, or rather the polylactic acid that you can get from the starch. This material is called PLA. The starch from the corn is fermented and turned into a polymer, he said. To produce the bags, the biopolymer is then mixed with normal plastic from fossil sources. And it is then biodegradable, the sales guy said. Sounds great, right! Only that it’s different than you might think.

Music by Dorian Roy

Anja: The people at the bag factory got their plastic pellets from Ludwigshafen, a grey city near the river Rhine in the west of Germany. There, one of the biggest chemical producers worldwide, the BASF, has several factories that basically stretch over an entire part of town. It’s very steampunk – big pipes wrapped in aluminum wind through the air and old and new factories stretch their chimneys into the sky. Almost fourty thousand people work here.

Why am I telling you this? I think for some reason I had believed that bioplastics come from some kind of organic farm. But as soon as I set foot in the factory, I understood that that was naive. Bioplastic is produced in the same big industrial settings that conventional plastics come from.

Carsten Sinkel and colleague, in German: Karl-Heinz, wieviel Grad hat der jetzt ungefähr?

Anja: I got to visit the BASF lab where new kinds of bioplastic are developed and tested – all top secret. Their chemist Carsten Sinkel explained to me how different monomers are turned into polymers by using catalyzers. Of course, I wanted to see the factory where the actual plastic for my bags was produced but they wouldn’t let me in. Construction work, they said.

The company had been producing biopolymers here since the late 90s. The name of the product was Ecoflex. Now the interesting thing is, eco flex was based on fossil fuels, but it was biodegradable. They now also produced a second product, Ecovio, the plastic used for the bags I was after. It was a mix of plastics from fossil sources and from renewable ones, the PLA from the corn starch.

Ambi

Carsten Sinkel, in German: Ja, also wenn man mal das Ganze aufmacht, dann sieht man hier, dass sowas ähnliches wie Tupperboxen, also sehr unspektakuläre eigentlich…

Anja: Chemist Carsten Sinkel also showed me their compost lab. And he told me about the caveat. This plastic only degrades quickly in an industrial composting plant, not in the ocean or in nature. It needs very specific conditions, a certain kind of humidity and a very high temperature, around 60 degrees Celsius which is 140 in Fahrenheit.

Music by Dorian Roy

Anja: Not long after I had visited the plant, a German environmental organization started publicly criticizing these plastic bags that I had researched. The Deutsche Umwelthilfe said that the slogans on the bags were misleading customers. And they had conducted a survey at industrial composting plants to see what they thought of the bags.

According to the environmentalists, the composters weren’t happy at all to see the bags in the bio waste. In Germany we collect our organic food waste separately. But now that people started putting bio plastic bags in there as well, the composters had a problem. The bags didn’t degrade well enough for their needs. So the composters tried to sort them out in advance. The bags weren’t actually composted.

I later also learned another surprising thing from a bioplastic researcher. There are not only fossil based plastics that are quote on quote degradable under very limited conditions. There are also plant based plastics that are chemically identical to conventional plastics. So that means that they will degrade as slowly, they’re chemically the same.

Sounds confusing? Well, it was. But what I took away was that bioplastics unfortunately don’t look like they are a solution to plastic pollution in our environment, especially not the oceans. Imagine how cold it is in the water or at the bottom of the ocean. Definitely not 60 degrees. And so I had to go look elsewhere for solutions.

Ambi

Clapping at conference

Moderator: Thank you very much, Alessandro. In all of our discussions we said, also we need industry on board. And therefore I would like to ask Martin Engelmann about his observations.

Martin Engelmann: Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman, thank you very much. I think through our commitment and participation here in the whole conference, we have shown that marine litter is one of the true global problems that the plastic industry is facing so far.

Anja: In 2013, politicians, scientists and industry experts met in my hometown Berlin for the International Marine Litter conference. Just a couple of months earlier a young Dutch guy had presented an ambitious and futuristic plan to clean the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. But at the conference, the consensus was that we would need to tackle the issue closer to the source, not in the middle of the ocean. But where exactly was the source of the problem? That was the dividing line.

Kim Detloff: Maybe a last sentence to the plastics industry. I’m really happy to have the plastics industry here, and I’m happy to see all these kinds of different measures and projects. But let me make a stance for your real producer responsibility. And I think it’s important to also discuss the reduction of plastic consumption in general.

Anja: Industry representatives would argue that the source of the problem was people carelessly littering or a failure of managing our waste. Some environmentalists and scientists, however, believed the source to be closer to our culture of consumption. Some even dared to question the amount of plastics we are producing and consuming each year. It’s about 400 million tons now, that’s comparable to the weight of all humans on Earth. In other words, every year, we’re producing one plastic human for each of us real humans. But the plastic humans will probably outlive us.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

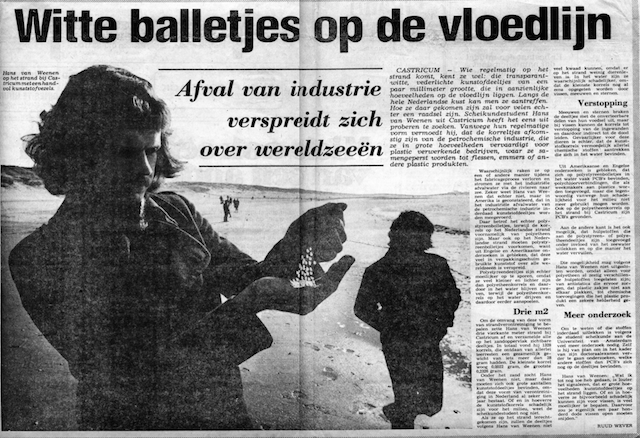

Anja: I also met this witty grey haired man at the conference whose story impressed me very much. Hans van Weenen from the town of Castricum in the Netherlands. Hans showed me little jars of plastic pellets that he had brought, collected at his local beach at the North Sea. But he hadn’t started doing that just now. He had been collecting plastic there since the early 70s.

Ambi

Hans and Marja van Weenen collecting plastic at their beach, in Dutch:

Hans: Het is een enorme verscheidenheid aan…

Marja: En een korreltje.

Hans: Ja. Granulaat. Een pellet.

Anja: When Hans was a kid in the 1960s, they already found little pieces of plastics in their bathing suits after going out to swim in the North Sea. When he started to study chemistry in the 1970s, he remembered the little plastic pellets. Together with his girlfriend Marja, he surveyed the plastics on some square metres of drift line by the water and he wrote a student paper on the trash he found. He read me parts of it.

Hans reading in Dutch

Anja: 23-year-old Hans had tried to extrapolate what his findings meant. In the literature he read that just two years earlier, scientists had found plastic particles in the middle of the North Atlantic. Hans also learned that the little plastic pieces he had collected on the beach were raw material. The pre-production pellets that get mold into new products, like the plastic bags in the factory I visited. Some people called them the mermaid’s tears.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja: Hans did try to draw attention to this. In 1975, he wrote an article for a Dutch chemistry journal. And a local newspaper also got interested and published a story. The title is very much like what you could read today. It said, “the industry’s trash spreads out over the world’s oceans”. Hans also talked to the director of a Fisheries Institute, he told me. But the director just said there was absolutely no reason to worry about these plastic particles. And so, young Hans thought – why should I go on with this? And he started to work on different issues.

But Hans kept collecting plastic on his beach. And he noticed that the composition changed. More and more colorful fragments washed up as well, from products torn apart at sea. And finally, there were the black pellets. They were black because they were recycled material, Hans told me.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Erik Zettler: Plastic is a new environment in the ocean. It’s only been around since after World War II. So like an exoplanet, this is a surface that we don’t really know the conditions there and we don’t really know how those conditions will interact with existing lifeforms. So in a way it is a new surface out there and we don’t understand how it’s going to ultimately be colonized by the things that are out there, or change the things that are out there.

Anja: This is Erik Zettler. Two years ago, I visited him and his wife Linda Amaral Zettler in Massachusetts. They are both microbiologists and worked in Woods Hole at two ocean institutes.

Linda Amaral Zettler: So my lab has been heavily involved in looking at microbial diversity in the ocean, partly through the census of marine life and specifically the International Census of marine microbes. And so we knew a lot about what was in the ocean, at least we thought we did – until we started looking at plastic.

Anja: Linda Amaral Zettler and Erik Zettler had found something quite amazing.

Erik Zettler: The surface was completely coated. You couldn’t see really the plastic surface hardly anywhere. It was coated with, you know, diatoms, these photosynthetic cells with beautiful ornate silica shells, and bacterial filaments and bacterial rods and spheres and sort of this mucilage, this sort of almost like gelatinous type stuff that a lot of these cells put out, this forms this biofilm that’s really a very diverse living community – it’s almost like a tissue.

Anja: The plastic in the ocean was teeming with life. There was a whole new world developing on it, a microbial world. Linda called it the “plastisphere”.

Linda Amaral Zettler: We discovered cells that seem to be directly interacting with the plastic surface. These pit formers, as we like to call them, they really seem to be forming pits on the surface of the plastic itself. And so that sort of begs the question, well, how are they doing that? Is it sort of an active process? Are they doing it intentionally to obtain some kind of energy from the carbon source of the plastic itself? Or is it perhaps just the result of some byproduct of their metabolism?

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja: In a sense we all now live on the Plastisphere. We created plastic, we use it in almost every part of our lives, every day and in huge quantities. And now we’ve realized that it has leaked into almost every part of our environment. It already weakens and kills thousands of animals – sea birds, turtles, seals, whales. It’s a great tragedy of suffering and lost lives. What are the consequences for us and for the ecosystems we depend on? And what do we need to do to solve the plastic pollution problem?

That’s what I want to explore in this podcast, by talking to the growing community of people who are digging into this – the science, politics and culture of our plastic world. And I hope you join me on my journey through the Plastisphere.

My name is Anja Krieger, and the music was produced by Dorian Roy and Blue Dot Sessions. The cover art was designed by Maren von Stockhausen. The first words in this podcast were spoken by Terry Shibuya, who I met at Kamilo beach.

My thanks go to the great people at our audio group, the Sonic Soiree Berlin, especially to Susie Kahlich, producer of the Artipoeus podcast, and Ines Blaesius, who gave me feedback on this episode. And I also thank the awesome crew at RiffReporter, our new collaborative ecosystem for freelance journalists here in Germany. If you understand German, check it out at riffreporter.de.

If you like this, go to Patreon and support the production. Or if you’re German, support me via Riffreporter.

I hope that you tune in for the next episode. Until then – refuse, reuse, repair and recycle. Bye-bye and Tschüss!

Music by Dorian Roy

Thank you for doing this podcast there are a lot of people who despite all the publicity in newspapers, magazines, Television are still not aware of the cost of pollution. Just got back from Florida- Plastic straws everywhere, Coffee Cups also served with straws at takeaways, plus plastic stoppers so the coffee does not spill. Water at restaurants also served with straws. The scientific and academia have come to an incorrect conclusion that they only way is to reduce and prevent the use of plastics. This does not factor in the huge amount already plaguing our planet or the daily inflow into our waterways and oceans. What also needs to be tackled is the actual removal of plastics. Would appreciate your looking at a 5 minute video http://www.orcaclean.com/video Although initially built to deal with oil spills it can easily deal with plastic on land and on waterways. It is also able to deal with invasive algae due to rising sea temperatures and excessive use of fertilisers. The ORCA can generate windspeeds of 180 kph like a tornado and is powerful enough to lift any plastic or algae without passing through any machinery thus avoiding any clogging or down time. Certified by ABS and Lloyds Register Type Approval. Ex-Boeing Wind Engineers and Marine Engineering went into this technology.