Sound installation Plastic_ity – by Saša Spačal

Anja

Can you hear the earthworms?

They are moving around, in the soil.

Music – Arlan Vale by Blue Dot Sessions

Saša Spačal

Everything that exists comes from it and it, like, grows from it. And everything that dies is decomposed in it. So, it’s a factor that has to be there and has to be alive with all the bacteria, all the little critters that can transform it into, really, living matter.

Anja

Welcome to the Plastisphere, the podcast on plastic, people, and the planet. My name is Anja Krieger.

Music – Valantis by Blue Dot Sessions

When we talk about plastic pollution, we often think of oceans and beaches. But plastic is literally everywhere. And that includes not only rivers, and lakes, but also the soil under our feet. The thin layer of ground that feeds all of us.

It’s not only the trash littering the parks and sideways. There are many ways plastic ends up in the soil. It can leak from factories and landfills, streets, rivers and washing mashines, and may come from packaging, paint, sneakers, tyres, t-shirts, even fertilizer.

For a long time, this terrestrial plastic has been overlooked. But now, it’s entering the spotlight. Scientists are starting to investigate the extent and impacts of plastic in the soil and in the ground. What do we know about them? That’s what I’m going to dig into in this episode.

Saša Spačal

The first thing that I learned, the first shocking thing was that there’s so little done about it.

Anja

I recently skyped with Saša Spačal, an artist from Ljubljana in Slovenia. Her most recent installation “Plastic_ity” deals with microplastics in the soil.

Saša Spačal

There is really not a lot of research about that. A lot of articles that we found, they were all just calling for more research, more research.

Anja

In her art, Saša deals with the human impact on the environment, especially the soil. She’s the one who recorded the earthworms I played for you at the start of the episode.

Saša Spačal

Earthworms are these special little beings that are able to go through all layers of the soil down to the rocks. So, they’re really in all layers. So, basically they’re able to transport plastics really, really far away.

Sound installation – Saša Spačal “Plastic_ity”

Anja

To illustrate this, Saša bought her own earthworms and microplastics. With a small underground microphone, she recorded the animals’ movements. She then arranged the different recordings into tracks of the composition you’re hearing right now. In her installation, Saša turns her earthworms into little DJs, who control the volume through their movements.

Saša Spačal

So it’s just, through interface of the sound, then the earthworms move the microplastics.

Music – Particle 2 by Dorian Roy

Anja

Saša’s artwork is inspired by real science. It’s based on an experiment that looked at the interaction of earthworms with microplastics. Biologist Matthias Rillig is the one who carried out the study.

Matthias Rillig

When we first thought about microplastic, actually, the first organism group that you think of, I think, is an organism that really, literally, eats soil. That’s what they do. They are geophagous, as it’s called. So they basically, as they move through soil, they ingest it. And in the end, they excrete it again.

Anja

Matthias runs the soil lab at the Free University in Berlin here in Germany. He’s very fond of fungi, bacteria, and of course, the earthworm.

Matthias Rillig

It’s also been called the whale of the soils, right, because it’s very similar when you think about it. These things sort of indiscriminantly – well, not completely indiscriminantly – but you can, you can imagine like a whale that just goes through and sort of grazes material and just ingests it, as it goes through. And that was kind of the, really, the first thing that we and also others thought about in terms of what it would be interesting to examine when you’re thinking about microplastic.

Music – Lumber Down by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

The idea came up seven years ago at the journal club Matthias held at his laboratory. His team came together to read interesting papers that might inspire them to find new research topics. One of these papers discussed microplastics in the ocean, a field of research that was generating growing interest and concern.

Matthias Rillig

But there was no mention of soil. And so we do work with soil and, well, we thought, why would this material basically not also occur in terrestrial environments. That’s where it’s mostly used and produced. So…I mean in hindsight, it’s fairly obvious. Then, of course, the next question was, that I formulated in a paper in 2012, is it worth thinking about microplastic in soil? And that’s not, that’s not exactly obvious because the effect of microplastic in the aquatic environment, more specifically in the marine environment, mostly hinged on the fact that they were particles – in an environment that is sort of not very particle-rich, because it’s aquatic.

Anja

Think about it this way: The oceans are vast bodies of water, where surfaces and particles are pretty rare. So just by being solid little rafts, plastics can have all kinds of effects there. They can collect pollutants from the water, attract micro-organisms, and animals often mistake them for food. But you can’t just assume the same things happen in the soil, Matthias says.

Matthias Rillig

Soil really is completely different because it is an extremely surface-rich environment, full already of particles. And it’s in essence just a vast amount of surface. So it is, I think, it’s not straightforward to sort of extrapolate from all the effects that had been found in the aquatic environment to what it might do in soil, because the situation is fundamentally different.

Anja

It is also much harder to analyze plastic in the soil than in the water. In his first paper, Matthias pointed out how little was known yet. “Given that microplastic likely is in our soils, can it have adverse effects?” he asked. He suggested that some soil creatures might grind down bigger pieces of plastic into even smaller ones. And the animals feeding on the surface might take the microplastics deeper into the soil.

But the strange thing was that, at first, nobody really seemed to notice his article. The plastic in the Pacific Ocean was drawing more attention from science and media than the trash right in front of us. It took two years for his paper to get one citation. However, it was eventually referenced more and more – as an increasing number of scientists became interested in the effects of terrestrial plastic pollution.

Music – Building the Sledge by Blue Dot Sessions

But what is soil, this ecosystem we are talking about? When I spoke to Matthias, I realized I knew nothing about it.

Matthias Rillig

It’s been called the most intensely 3D-structured bio-material on earth. It consists of solid material, minerals, organic matter, air that’s very different from the air above ground, water, water that’s very different and on which different forces act than free water – and of course the immense diversity of soil biota that all interact in very complicated and intricate ways, and they are all contained in this intensely three-dimensionally-structured fabric that is the soil. And that’s always fascinated me and I think a lot of other people.

Anja

The more prominent inhabitants of soil are earthworms, bugs, ants and centipedes. But have you met the smaller ones? I just learned that there can be more individual organisms living in just a handful of soil than the total number of people who’ve lived in human history. Like the tiny springtails which look like insects with their little antennas. Or the soil mites, the white potworms, or the pseudo-scorpion. On an even tinier scale, countless microbes including bacteria and fungi inhabit the soil, as well as filter feeders like ciliates and rotifers. Together, these little-known creatures form a complex web of life that builds and maintains the structure of the soil.

Matthias Rillig

Yeah, this is our sivving machine. It’s an amazing piece of equipment! But basically here we have little sives that contain our soil and also the aggregates from, for example, our microplastic experiments. And this is a standardized method that’s used everywhere in the world to assess the stability of these little soil crumbs.

Anja

In the lab, Matthias and his group of 50 scientists have specialized tools to analyze the structure of their soil.

Matthias Rillig

So that’s how they go in there and then basically it just very gently tumbles this material in there. So it’s a very gentle force.

Anja

What I learned from Matthias is that the structure of the soil is crucial. It’s the basis for all the life that lives in there. And microplastics, especially the fibers, could change this environment.

Matthias Rillig

You have to understand if there’s like a change in bulk density and some really fundamental property, like if these aggregates are stable or not, that is then automatically expected to have effects on virtually just about anything you could think of in soil, because that is so close to the heart of what soil is all about. This 3-D arrangement of the particles and the pore spaces that it leaves in between them that is the habitat for all the life.

Anja

So if microplastics change the physical structure of the soil, this could have ripple effects. For example, it could change the kinds of microbes that live in the soil. These microbes are not only central to our food and crop production but also have an effect on the global climate. Soil microbes provide the nutrients that plants need, and they help the plants fight off harmful pathogens. So the microbial community is crucial to soil fertility. What happens then if microplastics come in?

Matthias Rillig

My expectation is very firmly that, yes, this will for sure change also the community composition of microbes.

Music – Lumber Down by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

The science on plastic in the soil has just begun. And even though material has been piling up for decades, we don’t really know how much of it is there. One team of researchers estimated that in the EU, at least 4 times more plastic end up in the soil than in the ocean each year. It can get there through a multitude of ways. Polluted rivers can deposit plastic on their banks while the water makes its way to the sea. Particles, shreds and fibers have also been found in the sludge from wastewater treatment and biogas plants. This sludge is often sold to farmers, who use it to fertilize their fields. Feeding their crops, they end up pouring bits of plastic into the soil. In 2005, a biologist from Cornell University found that synthetic fibers were still found 15 years after the sludge was applied to the farmland. And one estimate says that agricultural soils alone might contain more microplastics than the (surface of the) entire oceans basins.

But plastic also reaches our soils in ways that I never would have been able to dream up.

Matthias Rillig

These particles can sort of also rain down and just fall out of the atmosphere. That’s just one study that showed this in the Paris metropolitan area and they found a rather astonishing number of particles per square metre and day that sort of just fell out of the air because it got entrained in dust, or I don’t know where that material really came from. But that’s pretty interesting because it also means that, if it’s really entrained in the air, then these materials can also essentially reach anywhere.

Anja

Up to 355 plastic fibers fell onto a square meter of Paris every day, researchers found in 2016. There was less fallout over suburban areas. But a new study shows that even high up in the Pyrenees mountains, far away from cities, the same amount of microplastics falls out of the sky each day as in Paris. Half of these microplastics are so small that we could inhale them. When they enter the soil, this could also have potential consequences.

Matthias Rillig

So when you’re talking about what effects are there for humans. I don’t really know. I’m not sure if anybody else knows but there’s two things maybe to consider. First of all, microplastic is expected to – but has never really been shown – to fragment into even smaller pieces of materials that are eventually then in the nanoplastic range, so much smaller than a micrometer.

Anja

It’s important to understand that materials in nanosize can acquire completely different properties than the original stuff they are made of. They can cross biological membranes and go into cells, which can make them more toxic, Matthias told me. Whether that happens in the environment with nanoplastics is still an open question.

Matthias Rillig

These nanoplastic particles, they could potentially be taken up into plant roots. And then there’s a possibility of this material to be translocated above ground. This has not been shown. So we don’t know if this occurs or not. And there is, owing to the huge surface that is soil, a somewhat decreased likelihood that this is a pathway of great importance – but we don’t really know yet. Then it would be in, potentially, plant materials that we as humans or livestock would eat.

Music – Beat 1 by Dorian Roy

Anja

Abel Machado has spent the past year trying to find out more. The oceanographer from Brazil came to Berlin to do his PhD. There he met Matthias, and joined the soil lab.

Abel Machado

I knew he was into plastic and I, I found him like a super nice guy and I was okay, I want to work with this guy and I know he’s into plastic. So let’s think about plastic and soils from a pollution perspective finally.

Anja

From the world of water, Abel ventured into the world of soil. I met him at the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology shortly before his departure to his new industry job in Brussels. Abel was excited to show me the results of his experiments with nanoplastic and vegetables.

Abel Machado

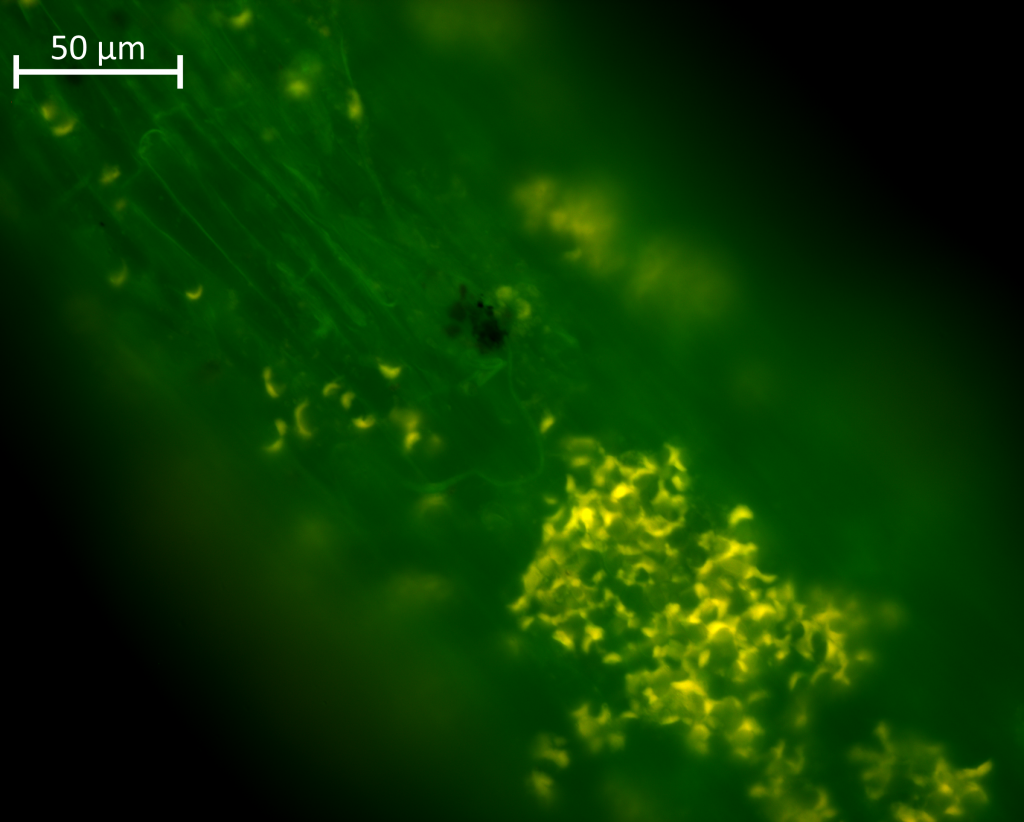

So this is more or less how you see a root in the microscope. So you see the green part here, it’s like, it’s a fluorescence microscope, so we kind of see the root shining. This is the cool thing. And then you see the green part here, are the root tissues, you see the divisions of the cells, the individual cells in there, right? And then we exposed this root to the plastic.

Anja

The root Abel showed me was the root of lettuce. The kind of lettuce we eat in our salad. Abel and his graduate assistant had grown around two hundred of these plants in hydroponic cultures, in little jars of fluid. Under normal conditions, lettuce can grow relatively well there, without soil but with water and the right nutrients. But the scientists had added nanoplastics – so small, that they’re impossible to see with the naked eye.

Abel Machado

So the roots, they have this very, very fine hair-like structures that they used to absorb water and the plastic just coats it completely. So that was very impressive to learn, and why this stays there after you washed it very much.

Anja

After the experiment, Abel and his colleague had washed the root very carefully, three times. Then they sonicated it, which is a method to really clean up the tissue with ultrasonic waves. But the nanoplastics were still there, visible as bright clumps under the microscope – each one containing uncountable particles. It was clear the lettuce did not like this diet. After only two days, its leaves were drooping, as if it were thirsty. And it grew less. The plant wasn’t acting healthy. But this was not the case for every plant.

Abel Machado

For the lettuce, the lettuce doesn’t like. For the carrots, the carrots didn’t care at all. So the plastics were there, the carrots were growing just as happy as they would without the plastic! And what seemed to be happening with the carrots is that other changes are happening. Like, the carrots are not physiologically, they’re not the same carrots with plastic and without plastic. But they don’t seem to be less healthy carrots. They just seem to be different.

Anja

We don’t know yet whether or not nanoplastics are indeed common in the environment. But if they are, they could have very diverse kinds of effects on the plants that we eat. And the results beg another important question:

Abel Machado

If the lettuce is absorbing plastic – because we know for sure it is interacting very strongly with the root, right? If it is absorbing, are there consequences for us? Because definitely, plastic like this has to penetrate multiple barriers that are very tough in the plant tissue, like, they have like cell walls and we don’t have cell walls. We just have cell membranes and these cell membranes are much easier to cross. So if they made through an organism that does have cell walls then they easily pass through an organism that has only cell membranes.

Anja

I asked Abel if he’d feel comfortable eating the lettuce he had fed with the nanoplastics.

Abel Machado

No, not with the nanoplastics. I normally avoid touching or like… even like… for the microplastics, I touch without gloves, when nanoplastics, I really avoid contact – because they are very, very reactive and we noticed that they stick to so many tissues.

Music – Arlan Vale by Blue Dot Sessions

Reinhold Leinfelder

Geologists would not treat these things which were man-made till recently, but now we see that we have so much of this stuff of man-made materials, we call it techno-fossils or technosphere, in the environment, and plastic materials are one of the very important ones. So we can’t ignore them anymore, we have to treat them like a normal sedimentary particle. And we have to think, where do they come from and how are they transported, can they be eroded, can they be resedimented and where will they finally be sedimented and what’s the fate then of this material. Will this remain forever or will this dissolve? Things like that.

Anja

At Free University of Berlin, I met Reinhold Leinfelder, a geologist who has taken an interest in plastics. His field of research is the ground, as well. But in contrast to the living system of the soil, he’s looking at stones and sediments, and what they tell us about the past. Plastic, he thinks, will become part of the record that future geologists will discover in the sediment.

Reinhold Leinfelder

Once it’s embedded in sediments, it can be very, very long-lasting. So depends on the type of sediments where plastic lands in, when it’s very fine, if it’s very fine and maybe if it’s in an area where there’s less oxygen, it can last very long. We have organic materials, much weaker ones which are hundreds of million years old.

Anja

Today, some beachrock already contains plastic, Leinfelder told me. But even if the plastic doesn’t last and dissolves one day, it could leave molds or casts. They could stay hollow, or be filled with another material like small crystals of calcite. Leinfelder thinks there is a very good chance a lot of the plastic will be preserved this way. It could even become oil or gas again, he thinks. In any case, the plastic will leave traces in the ground. And because many plastic products are around only for a short time, they could enable future geologists to date sediment layers in finer ways than ever before.

Reinhold Leinfelder

Going to the Teufelsberg for instance, where about one third of the war debris of Berlin has been piled up from 1950 to 1972 – we also find plastic there and different kind of plastic and we can find out whether it was post-war or pre-war or during the war. And we just happened to find a a small box of plastic which turned out to be a condom box and with a certain label on it, since it was packed in a plastic box and not in an aluminium box – this would have been an earlier one – we could really say that this was sedimented from a time span of 1968 to 1972. So this is a four-year precision which we normally don’t have in geology. So it’s just one example with a twinkle of the eye, to say well, we really can use this plastics for really fine stratigraphy and for correlating lots of timelines, yeah.

Music – Groove by Dorian Roy

Anja

Of course, what further helped Leinfelder to date this finding so precisely, was the fact that what had seemed like a genius idea at the time, turned out to be a nightmare upon closer inspection. Because the kind of protection the condom offered wasn’t really the best idea.

Reinhold Leinfelder

So this product then was a very rapidly out of sale because it was found out that there was a lot of mercury inside in order to prevent syphilis. So this is very toxic, of course, and then it was forbidden from more or less one day to the other. So this knowledge does help us to really define then the age of this finding here in the sediments, yeah.

German blog post on Leinfelder’s finds on Teufelsberg (literally, “devil’s mountain”)

Anja

Techno-fossils like this one could help the people of the future understand what our specific time period was like. And if plastic and other traces of our society might indeed last so long, they could mark the on-set of a new geological era – an era which has been discussed among geologists for two decades now.

Reinhold Leinfelder

And it was in the year 2000 in Mexico where they all gathered again and Paul Crutzen, Nobel Prize laureate – we owe him the knowledge about the ozone hole – he just couldn’t hear it anymore and he got up, he said “we are not living in the Holocene anymore!”. The Holocene is the geological time from the last Ice Age to the present. So officially, we are living in the Holocene. He said, “this is not the Holocene anymore,” and he was fumbling for words, so as he told us himself. “And this is the Anthro…Anthro…Anthropocene”. And so there was the word. But what he meant with it and what he insinuated with all that – he said, okay, the Earth system is different, we have a different Earth system and its men-made, its human-induced, that there are such big changes. And by using a term which sounds like a stratigraphic term because we had the Pleistocene and the Holocene and so before and now the Anthropocene means that he sees humans not only as a Earth system factor, but also as a geological factor. So that was another thesis which has to be proven that we see it in the sediments, that we have become a geological factor. And then he didn’t stop with that. He said, we have to do something against it, and it’s not only politics which are able to do something, and we also need science and we need technology in order to find solutions for that. So it was a claim to establish a new geological time.

Music – Aourourou by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

And the plastic we leave behind in our soil and sediment might become a marker for this new time in Earth history.

Saša Spačal

People talk about plastics, but they don’t realize how it’s really in the environment connected to the whole environment, what it does in there.

Matthias Rillig

We really just have scratched the surface of the effects of this material in soil and we constantly wonder is there something that we have overlooked.

Abel Machado

It’s very difficult by now with the very few examples we have studied to forecast what is the total effect in the ecosystem. But we can say that there is a very strong potential to change fundamental properties of the soil that are important for the way these species interact in the soil.

Anja

The soil we depend on is under threat. It is said that we only have 60 years of topsoil left. It is affected by climate change and global warming, agricultural techniques like saline irrigation, and monoculture cropping depleting it of nutrients. The heavy machinery of farming also impacts the soil, as well as herbicides and pesticides, and a variety of environmental pollutants. Plastic is just one of them, the one we have just discovered. We still know little about how the diversity of polymers, from fibers to fragments to beads, from macro to micro to nano size, will impact the soil. But we might induce changes that could last for hundreds of years or even longer. So, we better think about them carefully.

Reinhold Leinfelder

I fear it still takes quite some time until we properly act. That means the next sediments will be very full with plastics even in the marine realm, plastics, other debris, man-made debris, human-made debris like concrete, like aluminium.

Anja

Reinhold Leinfelder has no doubt, traces of our society will be visible even in the far future. But he’s an optimist, and so, his dream is, that the record will show that we made it. That layer by layer, we humans were able to transform our societies, to create a truly circular interaction with nature, and to leave less and less trash in the ground.

Reinhold Leinfelder

So that is my vision or my hope that there will still be enough traces of humans and of the Anthropocene. But that we would enter a post-plastic Anthropocene.

Music – Plink by Dorian Roy

Anja

This was the Plastisphere with Saša Spačal, Matthias Rillig, Abel Machado, and Reinhold Leinfelder. Many thanks to them for sharing their research and thoughts on the podcast. I’d also like to thank Julie Comfort and Brooke Watkins for feedback on this episode, and Joachim Budde for editing the German summary on RiffReporter.de.

Thanks to Sedat Gündoğdu and Sam Athey for recommending papers on plastic in soil via Twitter, and to the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science for helping me access studies on the subject.

My name is Anja Krieger. The music was composed by Blue Dot Sessions and Dorian Roy, and the cover art was designed by Maren von Stockhausen.

I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can find the transcript, links and additional information on the project website plastisphere.earth. If you have questions or comments, you can write me via e-mail, twitter or instagram @PlastispherePod.

Please support my independent production on Patreon. It’s only with your help that I will be able to sustain this project. You can also support me via Riffreporter, our ecosystem for freelance journalism here in Germany.

I hope you tune in for the next episode. Until then, visit a forest, dig in the soil, and greet the earthworms – Tschüss, bis nächstes Mal!