Lilly Platt

Well, we need to do something about it. We’re not going to do something about it tomorrow, we’re not going to do something about it yesterday, because we’re going to do it today! Because there’s no planet B. We only have this planet. And this is our Earth. We only have one chance.

Music – Plink by Dorian Roy

Anja

Welcome to the Plastisphere, the podcast on plastic, people, and the planet. My name is Anja Krieger.

Plastic pollution might be the most visible environmental issue we face today. But there are other kinds of pollution, and they are far harder to see. Like the huge amount of greenhouse gases that we emit into the atmosphere. These gases cause huge changes in our climate, with impacts that could last for millenia, and affect many generations to come. So in this episode, I’ll explore the connections between plastic pollution and climate change. Are these two issues buddies or enemies? Does plastic help or hurt our efforts to tackle climate change? Well, as with many relationships: It’s complicated.

This summer, I heard that some ocean scientists were getting weary of talking about plastic pollution. A Swiss professor called it a “media hype” in an interview. And I read an op-ed that stated that plastic pollution is an issue, but by far not the worst. I wanted to learn more, so I contacted the author, Nikolaus Gelpke. He’s a marine biologist and founder of a German publishing house devoted to the oceans called MARE.

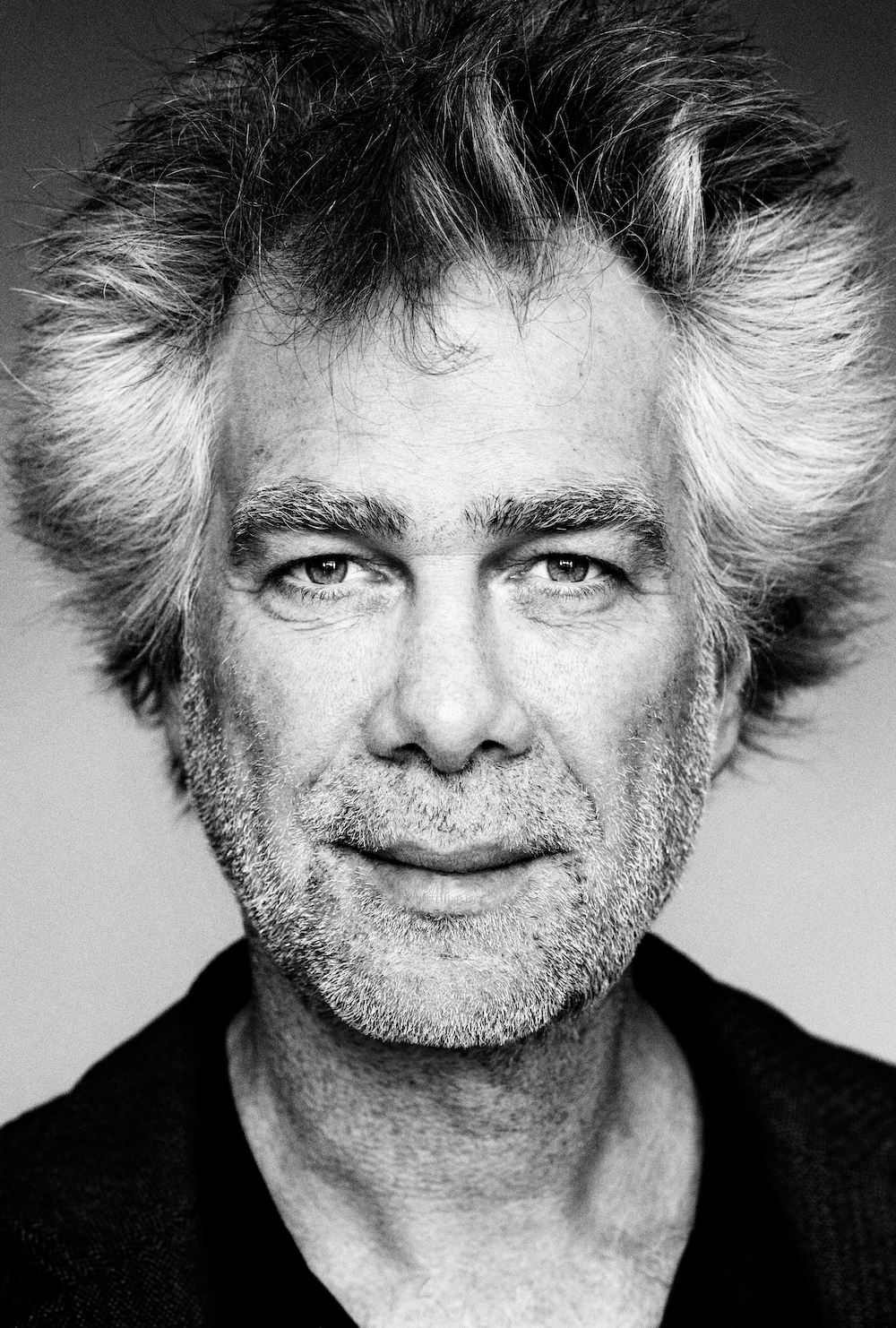

Nikolaus Gelpke

Absolute the crucial issue for the ocean is climate change, and not plastic. But if you compare how many media are talking about plastic and not about the problems from climate change, then you get really upset, because it’s the wrong message. It’s the right message, on one hand, because, of course plastic is a huge problem – but it’s not the problem. (…) You must see that the ocean organisms are balanced over millions of years to a certain pH and to a certain temperature. If you change the temperature of a human being from 37 degrees to 38 degrees, he has fever. If you change the temperature in the ocean for one degree, everything changes.

Music – Solear Interlude by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

When we emit carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, they trap heat in the atmosphere. Most of this heat is absorbed by the oceans, sparing us from higher temperatures on land. But for the ocean’s ecosystems, the warming has severe consequences. As the water expands, the sea-level goes up. And fish, squid and lobsters flee to cooler and deeper places. Fisherfolk don’t find them where they used to. According to the news agency Reuters, it’s like an “epic refugee crisis among marine life”.

Unfortunately that’s not the only climate impact to worry about. And that’s because the oceans also absorb some of the carbon dioxide itself. When this gas gets mixed into the water, it starts a complicated chemistry. What basically happens is that the CO2 turns into carbonic acid and changes the pH of the seawater, making it more acidic. And this is a huge problem for many organisms in the oceans, like corals, shellfish or plankton. Creatures that depend on a stable pH in order to make the calcium carbonate for their shells and skeletons.

Nikolaus Gelpke

If the phytoplankton loses the calcification, then you have killed one of the key animals or key organisms of the food chain. This is of course a completely different problem than to lose some sea birds.

Anja

So are we talking too much about plastic and too little about the more certain risks of climate change? I checked Google Trends to compare which topic is searched for more on the internet. It turned out that the term ‘climate change’ still gets way more attention than ‘plastic pollution’. But what I also found was that plastic has recently become the most searched for topic in regards to the oceans. If you compare the Google searches, plastic gets much higher attention than, for example, overfishing or climate impacts like ocean warming and acidification.

Music – Valantis by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

The science on plastic pollution is still pretty new, and has only taken off recently. The litterbase, a website by the Alfred Wegener Institute, has tracked the studies on marine plastic and trash. For a long time, only a few studies were published each year. But the past decade has brought an exponential increase of research. Scientists have started to address the many open questions. Like, how plastics could impact the food chain. They are still at the beginning, and searching for answers. Plastic could turn out more benign or more dangerous than we think now. But while we explore the unknowns of plastic, let’s keep in mind that our oceans face a lot of other issues – and that one of the biggest ones is climate change.

Music

Plastic pollution was like an entry point for me. An opener to the huge global changes we humans are causing on our planet.

I can still remember the moment I really started thinking about this. A couple of years ago, I visited the German island of Juist in the North Sea for a radio report on plastic. I did the usual thing reporters do there – I documented a beach clean-up, I talked to the islanders, and I consulted some experts. One of my interviewees was Bernd Oltmanns from the Wadden Sea National Park. I asked him about the importance of plastic pollution. And he said it mattered, but then he went on to tell me about another issue he was worried about.

Bernd Oltmanns

Was wir zur Zeit nicht abschätzen können, ist beispielweise die Belastung, die auf das Wattenmeer zukommen über den Klimawandel…

Anja

Oltmanns told me about the potential impacts of climate change on the wadden sea. If you haven’t been there, it’s these large stretches of sand that are exposed parts of the day, and then taken up by water again. So the creatures there live with the coming and going of the tides and they are finely adjusted to that. Some of them might just not be able to deal with climate change, with the stormfloods and changes in their sediment, Oltmanns told me. It was only a brief exchange, but it stuck in my head. My understanding of climate change was still quite blurry, so I decided to learn more. Through plastic, I started to understand climate change. And I’m not the only one.

Music – Lumber Down by Blue Dot Sessions

Lilly Platt

Well, it all started in 2015 when me and my grandpa were walking to McDonald’s and every day there was a lot of plastic there. And we thought, should we pick this up? Cause it’s been there for a long time –

and that’s how the plastic part started. But how the climate change part started, it was only, I think, a few weeks ago!

Anja

That’s Lilly from the Netherlands. She is a plastic pollution activist, actually one of the youngest that I know. Lilly started picking up plastic trash with her grandpa when she was seven. He’s a geologist, and together they explored how plastic can travel to the sea, break into tiny pieces and harm animals. Lilly’s mom joined them, and together the family collected trash and shared their finds on social media. They called the project ‘Lilly’s Plastic Pickup’.

Lilly Platt

And after each pickup, we take a picture of it. So, we separate pieces of plastics, so we put the bottles with the bottles, the cans of the cans, and… yes.

Anja

Soon Lilly’s pictures online gained a larger and larger following. She became ambassador for the Plastic Pollution Coalition, and got invited to speak at a conference in Norway. A conference that was held in honor of a whale that had stranded there the winter before. It was a Cuvier’s beaked whale, only the second one ever seen along the coast of Norway.

Lilly Platt

They didn’t know what to do so they had to shoot it, then when they cut it open they found the plastic inside. So then the conference started. So we went to Norway. And then, we went to an island – and the first thing you saw, it wasn’t the grass of the island or the rocks. The first thing you saw was just all the plastic and rubbish. And I picked up a piece of plastic, and it has been there for so long, it just crumbled in my hand.

Music – Valantis by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

One day in the late summer, Lilly’s mom came home with a link to a video by another young activist. It was Greta Thunberg, a 15 year old girl from Sweden. She stood outside, with long braided hair, in what looked like a forest, and addressed the camera.

Greta Thunberg’s video

We are on school strike for the climate. Every Friday we will sit outside the Swedish parliament until Sweden is in line with the Paris agreement. We urge everyone to do the same, wherever you are, sit outside your parliament, or local government building until your nation is on a safe pathway to a below two-degree warming target…

Lilly Platt

And she was talking about the Paris Agreement and that the government should follow it and that the temperatures should stay 1.5 to keep the ice from melting and so that there will be no rising sea levels. And then I thought, OK, I need to support her and do this. So then on Friday that week, we went to the government house to do school striking. Because every Friday, it’s Friday for Future.

Music – Tidal Foam by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

Lilly and Greta also started exchanging messages, and soon met for school strikes in the cities of The Hague and Brussels. They sat together, and they talked about the impacts of climate change, Lilly told me.

Lilly Platt

Well, I said that what do you think is the worst thing of climate change, which is the worst thing out of deforestation, melted icecaps, rising sea levels? And she says, all of them, because once they reach their peak of power, there’s no stopping it. We can’t go to the past to stop it. We don’t have a time machine to do anything. So, that’s why we need to stop it – today.

Anja

And Greta also thought about plastic. “Plastic pollution is horrible and an enormous problem,“ she wrote on Twitter. “But at least we can see the problem. CO2 is a lot worse, because it’s invisible. Imagine if we could see the CO2 polluting our atmosphere, then we would probably stop burning fossil fuels straight away.”

Plastic pollution is horrible and an enormous problem. But at least we can see the problem.

CO2, is a lot worse, because it’s invisible.

Imagine if we could see the CO2 polluting our atmosphere, then we would probably stop burning fossil fuels straight away. #climate— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) 13. Oktober 2018

Music – Lumber Down by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

So as you can see, plastic pollution and climate change are issues that can compete or cooperate to get our attention. But they also interact in a very direct and physical way. I was reminded of this when I recently listened to the 8 million podcast. It investigates the issue of plastic pollution and waste management in Asia. One episode talks about the many kinds of different plastic types which make recycling a huge challenge. And Doug Woodring from the Ocean Recovery Alliance says:

Doug Woodring / 8 million podcast

So how did we get there? Partly we got there to the effort to reduce climate change, that is an unintended consequence, because everyone wants to lightweight. Lightweight this, lightweight that, get transportation costs lessed. And by doing so the only material you can get straight into is plastic.

Anja

I thought this was really interesting. Does this mean that our immense use of plastic is partly due to our efforts to combat climate change? Plastic makes cars, airplanes and consumer products lighter, and that saves fuel and carbon emissions. Plastic packaging can also keep food fresh for a longer time. I also learned that many of the huge rotor blades of wind turbines are made with plastic, as well as solar panels. So it seems to be a really important material for our renewable energy sector. A recent BBC podcast even asked whether the anti-plastic movement actually harms the environment more than helping it.

Music – Groove by Dorian Roy

Anja

The calculation is a tricky one. Yes, you can estimate how much more you’d emit if you replaced plastic with other materials. The industry association PlasticsEurope actually published a study on this in 2010. It concluded that replacing plastics with traditional materials could cause around 60 percent more greenhouse gas emissions and lead to a greater amount of waste.

But what if this hypothetical scenario is too simplified? Maybe plastic enabled consumption patterns that without it would never have emerged. Like the amount of food we ship from far away, or the amount of car rides and flights we take each year. Maybe we wouldn’t be consuming so much, if plastic hadn’t made it possible?

And then there is the question of how much greenhouse gas is actually produced by plastic itself. First of all, plastic production is an energy-intensive process and releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. And then, gas and oil is also the raw material to make most plastics on the market. According to one estimate I found, between 4 and 8 percent of global oil go into plastic production. And that doesn’t include the plastic made from gas. And with the growing plastic production, plastic could use more and more fossil fuels over time.

But let’s take a closer look: The energy used obviously causes greenhouse gases, but what about the material itself. Isn’t it a good thing that plastic is believed to last for a very long time? That would mean that the carbon in the fossil material is locked into a very long-lasting object. And this way, it couldn’t pollute the atmosphere, right – as long as we don’t burn it.

Well, that’s what we thought. Until a new report came out, which showed that our plastic products also produce gases that can warm the atmosphere.

Music

This was recently discovered by scientists from the university of Hawaii in Honolulu. Sara Ferrón and Samuel Wilson, two researchers there, were trying to find out how much methane is produced by seawater. Methane is a very strong greenhouse gas, much stronger than CO2, and it can be produced biologically in seawater. But when the two researchers examined their results, they found a much higher concentration than they had expected. They were puzzled. But then they turned to the plastic bottles they had stored their samples in.

Sarah-Jeanne Royer

So this is the first time that they realized then that methane was being produced by plastic.

Anja

This is Sarah-Jeanne Royer who told me the story, when we spoke via Skype. She’s a Canadian oceanographer and joined the lab in Hawaii three years ago.

Sarah-Jeanne Royer

I read the reports and I was like: This is really interesting, I want to study it! And that’s where I started my journey with the greenhouse gases emitted from plastic.

Anja

So Royer and her colleagues filled a bunch of quartz vials with water and plastic, and brought them up to the roof of their institute. After two weeks in the tropical sun, they measured the production of greenhouse gases. And they found that all the kinds of plastics they had tested produced methane and ethylene, two greenhouse gases.

Sarah-Jeanne Royer

So from there on we decided to focus only on low density polyethylene, LDPE. And the reason for it, is because it’s producing the highest concentration of greenhouse gases. But it’s also in the world the most produced, consumed and discarded type of plastic in the world. This means then it’s highly used in the single-use plastic industry, which a lot of it ends up in the ocean and on the beach and on the coastline of many regions in the world.

Anja

You probably have a bunch of things at home made from this kind of plastic. LDPE is used for six-pack rings, plastic bags, packaging, and the coating of electrical cables. There’s a lot of other applications. Sarah-Jeanne Royer and her co-authors believe that it’s the weak structure of this polymer that causes it to degrade quickly and produce so much gas. They also found that the surface area of the plastic really matters: The smaller the pieces, the more greenhouse gases they produce, relative to size. But there’s another and even more interesting conclusion. The researchers found that plastic emits more greenhouse gases in the air than in water.

Sarah-Jeanne Royer

As oceanographers, we started with plastic submerged in water. But then we did the same experiment with plastic in air, and we realized then, okay – plastic pollution in the ocean is something. But then if we think in terms of all types of plastic that is exposed at the moment to solar radiation on all the continents in the world, this gives me shivers… like we don’t only focus on plastic pollution in the ocean anymore, but we have to focus on all types of plastic in the world that we use on an everyday basis – and also the plastic along the coastline, the landfills, the greenhouses, as well, that use a lot of polyethylen to protect our vegetables for example. So a lot of it is being used everyday and in contact with the solar radiation. So this made me believe then, okay, maybe I should be a little bit more careful about the use of plastic and making on an everyday basis. We think in terms also of cars, of cell phones, everything that we leave outside in the full sun, all day long might have an effect eventually on the emissions of greenhouse gases.

Music – Solear Interlude by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

There are a lot of ways we humans emit methane into the atmosphere. It gets produced by the stomachs of cows, the microbes on rice fields, through fracking and coal mining or the burning of biomass. So how big is the contribution of plastic, and is it relevant at all? Sarah-Jeanne Royer and her colleagues expect the methane production of plastic to be actually small in comparison. But they say that the role of degrading plastic needs to be further investigated.

I wondered what a climate scientist would say about the study and its relevance. So I contacted the Institute for Climate Impact Research in Potsdam here in Germany, and met with one of their scientists, Gunnar Luderer.

Gunnar Luderer

Yeah, first of all it’s a very interesting insight that experimentally the colleagues found hydrocarbons to be produced from the decomposition of plastic material. So that’s, that’s quite important.

Anja

I had sent Luderer a couple of figures from the paper on ‘production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made’. Based on that, we tried to figure out a rough upper estimate of the potential amount of greenhouse gases that could leak from the plastic. If all the carbon from all the trash we’ve produced up until today gets oxidized into CO2 that would about triple the overall mass, Luderer explained to me. So the roughly 5 billion tons of plastic waste in the environment would translate to 15 billion tons of carbon dioxide.

Gunnar Luderer

And that’s not insignificant. That’s about half the yearly energy-related CO2 emissions – if all that plastics that have accumulated over the past decades, if that was oxidized into carbon dioxide. But at the same time it’s also not a dominant source either. So, but that gives us a rough idea of what we’re talking about.

Anja

Of course our calculation was highly simplified and hypothetical. We assumed that the plastic that had accumulated overtime in landfills or the environment would turn into carbon dioxide. But the researchers in Hawaii had actually found it to produce methane, and ethylene. And we had only estimated the plastic waste, when the results from Hawaii suggested that plastic objects still in use could also emit greenhouse gases. When I asked Sarah-Jeanne Royer, she actually told me that it’s not possible at this point to provide a good estimate on the amount of greenhouse gases from degrading plastic. Too much data is missing, she said. To understand the actual contribution of plastic to climate change, we’d need to know much more about the type of plastic, the environment it ends up in, and how much sunlight reaches it. Just like the size of the plastic pieces, these factors influence the chemistry. Is it an issue we need to investigate further? Yes, definitely, climate scientist Gunnar Luderer said.

Gunnar Luderer

It’s fair to say that we’re conducting a giant uncontrolled experiment on the Earth system by depositing these very large amounts of plastics into the environment. We don’t really know where this stuff ends up, we don’t really know the fate. We don’t really know what exact amounts end up in the oceans, what exact amounts end up in other components of the Earth system, and we don’t fully understand what physically happens to these plastics, what the chemical consequences are, what other substances get produced from this plastic debris, and we don’t fully grasp the biological consequences for the biosphere. And this is certainly a very worrisome development.

Music – Taoudella by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

So back from my first journey into the relationship between plastic and climate, what are the take-aways?

The first thing is that plastic pollution is just the most visible form of environmental pollution, but definitely not the only one. It remains to be explored what its impacts will be. But no matter what the result, plastic can act as an entry-point, an issue that helps us understand the kinds of changes we are currently causing on our planet.

Like climate change, which we already know more about. And what we know is extremely worrying. Some of the greenhouse gases we emit today could still be in the atmosphere in thousands of years. And they raise the temperature of the water and on land, make extreme weather events more likely or intense, and cause ocean acidification and warming, with severe consequences for the ecosystems we depend on.

Plastic contributes to this climate change, because its production and waste release greenhouse gases.

But it also enables us to produce light-weight products, to make cars and planes more fuel-efficient, and to produce solar and wind energy.

So, as I said in the beginning: It’s complicated.

But what does it all come down to? We produce hundreds of millions of tons of plastic and emit tens of billions of tons of CO2 each year. Is there a deeper connection between plastic and climate change, maybe even a common root?

Gunnar Luderer

I definitely think that the plastics problem and the climate problem are two sides of the same coin. In the end it’s about our metabolism, the way we use energy, the way we put materials through our industrial processes. And tackling the climate problem will inevitably also have something to do with adjusting lifestyles and adjusting styles of material consumption and being more conscious about what we need, what we consume both on the material side, and on the energy side.

Music – by Blue Dot Sessions

Anja

Nature is based on a circular economy. We humans, on the other hand, have created a society that does not work in a circular way. We have taken oil and gas out of the ground, cut down forests and turned them into fertilized farms, we have covered the ground with asphalt and cement, and created a myriad of chemicals and plastics. In doing so, we have pulled huge amounts of resources out of the natural cycles. It has brought us progress, for a brief moment in time. But we haven’t thought it through until the end. Instead of closing the loop, we are producing all kinds of waste and stuff our ecosystems just cannot digest.

So to tackle climate change, plastic pollution, biodiversity loss and all the other pressing issues, we have to dig out their common root, and plant something new.

Music – Plink by Dorian Roy

Anja

This was the Plastisphere with Nikolaus Gelpke, Lilly Platt, Sarah-Jeanne Royer, and Gunnar Luderer. Many thanks to all of them. My special thanks go to Lilly’s mother, Eleanor Platt and to Ines Blaesius, Kathleen Mar, Sasha Chapman and Christian Schwägerl for feedback on this episode.

My name is Anja Krieger, and the music was composed by Blue Dot Sessions and Dorian Roy.

I’d also like to thank Marcy Trent Long of Sustainable Asia for permission to use audio from the 8 million podcast, Melanie Bergmann of the Alfred-Wegener Institute for data from the litterbase, and to Laura Markley, Simon Hirsbrunner, Martin Wagner, Kennedy Bucci, and Alicia Mateos for inspiration and help via twitter.

I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can send me questions and comments via e-mail or twitter @PlastispherePod.

If you like the podcast, please support my independent production on Patreon or – if you speak German – on Riffreporter.

If you want to dive deeper into the connection between plastic pollution and climate change, I can recommend to read the “The Plastic Backlash”, a long and insightful article in the Guardian. And the “Plasticphobia” episode of Costing the Earth, a podcast by the BBC, is also very much worth listening to.

By the way, after the interview with Lilly, I also started participating in #FridaysForFuture, to support the youth movement for climate action. Just so you know.

I hope you tune in for the next episode of the Plastisphere. Until then, rethink plastics. It’s just one piece of a big, big puzzle.

More on the plastic-climate nexus:

„The burning of waste is a key contributor to climate change.“ https://t.co/lzRPsJ9KTG

— Plastisphere Podcast (@PlastispherePod) 8. Dezember 2018

Climate change(CC)itself also increases plastic pollution in the oceans. How?Extreme rain and flash floods!While the plastics cause CC during both production and consumption,the changing climate increases the amount of plastic in the sea. It is worth mentioning these two together

— Sedat Gundogdu (@gundogdu_sedat0) 8. Dezember 2018

— Sedat Gundogdu (@gundogdu_sedat0) 8. Dezember 2018

Made me think of this video, shared by @SabinePahl I think https://t.co/SfVEHTxtm6

— Plastisphere Podcast (@PlastispherePod) 8. Dezember 2018

Watched half of "Plastic Ocean" yesterday and learned that the big Hong Kong pellet spill happened during a Typhoon, when six containers fell into the sea. So with more intense storms, this could happen more often, I'd guess: https://t.co/ZmsKpxq8n0

— Plastisphere Podcast (@PlastispherePod) 9. Dezember 2018

"Put simply, you can’t separate the effects of melting ice, chemicals, and plastics on bears, gulls and people."

Inspiring read by @looseuterus https://t.co/0M4ZESepd8— Plastisphere Podcast (@PlastispherePod) 12. Dezember 2018

What terrifies me… People arguing climate breakdown trumps plastic pollution. Both are dangerous outcomes the same global petroleum economy… https://t.co/cCmNPql6ZF

— Deirdre McKay (@dccmckay) 13. Dezember 2018